This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness and notoriety factor in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 42:

= James Worthy, Los Angeles Lakers

= Ronnie Lott, USC football

= Ricky Bell, USC football

= Walt Hazzard, UCLA basketball

= Don MacLean, UCLA basketball

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 42:

= Connie Hawkins, Los Angeles Lakers

= Kevin Love, UCLA basketball

= Lucius Allen, UCLA basketball and Los Angeles Lakers

= CR Roberts, USC football

The most interesting story for No. 42:

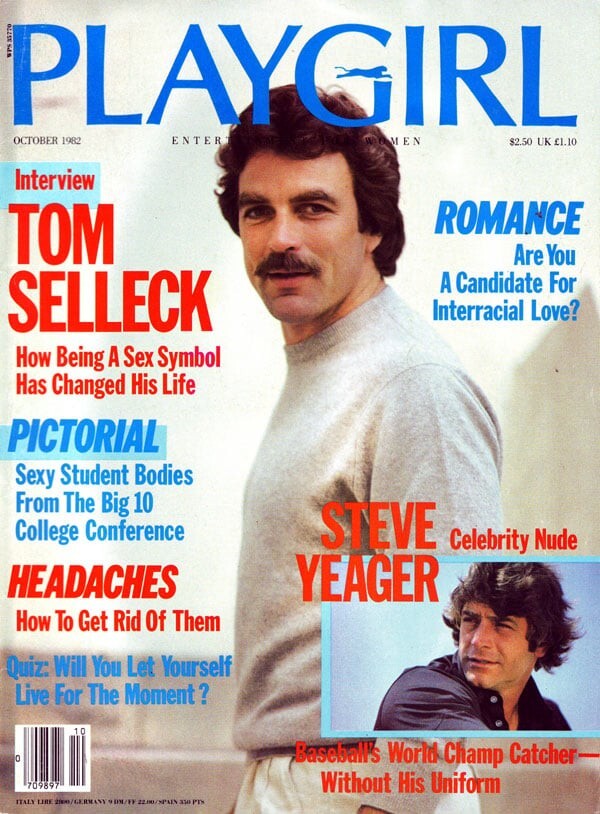

Tom Selleck, USC basketball forward (1965-66 to 1966-67) via Grant High of Van Nuys and L.A. Valley College

Southern California map pinpoints:

Sherman Oaks, Van Nuys, Los Angeles (Sports Arena), Hollywood

The 42 preamble

In November of 2014, UCLA announced it would retire the No. 42 across all its men’s and women’s sports teams. It was following up what Major League Baseball did 17 years earlier, this time to honor one of its most noteworthy alums, Jack Robinson.

UCLA may have also been nudged by another local university for the concept of this kind of number retirement. In February of ’14, Cal State Northridge’s athletic department retired the No. 58 among all its sports programs to mark the year — 1958 — when the school opened.

Conveniently, the timing for UCLA’s declaration marked the 75th anniversary of Robinson’s arrival as a student-athlete on the campus.

After two years at Pasadena City College, Robinson, out of Muir Technical High, went to Westwood in February of 1939 on an athletic scholarship. He departed in the spring of 1941, a few units short of a degree and with no graduation. The story goes that Robinson needed to make some income to help his family in Pasadena. He would soon go into the military.

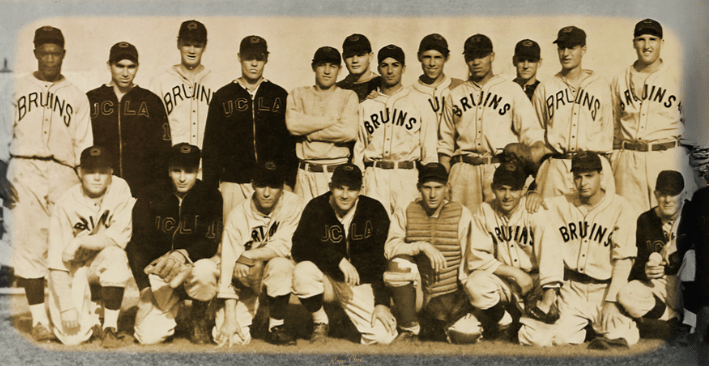

But Robinson sure did put a spotlight on the university. He was the first four-sport letterman in UCLA history – football (1939 and 1940), basketball (1940 and 1941), track and field (1940) and even a little baseball (1940).

Even more convenient was UCLA announcement’s was just after the success of the 2013 film, “42.”

The late actor Chadwick Bozeman played Robinson on his journey through Pasadena to UCLA, to the Dodgers’ Triple-A Montreal Royals, before it was decided he was equipped to join the Brooklyn Dodgers and wear that number 42.

The fact that Robinson never wore No. 42 at UCLA in any sport seems to be beside the point. UCLA’s accounting department acknowledges that as it finds places in almost every athletic platform to make sure a “42” is branded somewhere.

“Jackie Robinson established a standard of excellence to which people the world over should aspire,” said athletic director Dan Guerrero, a former UCLA baseball player, during the announcement. “We want to ensure that his is a legacy to be upheld and carried forward by Bruins for generations to come. While he wore several numbers at UCLA, Jackie Robinson made the number 42 as iconic as the man himself. For that very reason, no Bruin will be issued the number 42 — in any sport — ever again.”

For UCLA basketball, he was No. 18. For UCLA football, he was famously No. 28. What he wore playing baseball, the Bruin statkeepers still aren’t sure.

We had sought out UCLA’s sports information department for more info, but it can’t find any evidence he even wore a baseball number. The Dodgers and the Baseball Hall of Fame’s research department in Cooperstown, N.Y., didn’t produce anything. Neither did a dig through the Amateur Athletic Foundation nor the Pasadena City library archives. Employees at the Jackie Robinson Foundation finally were asked to quiz Rachel Robinson about it. She replied: I don’t know.

For now, it remains an iconic, and ironic, mystery. Which seems pretty twisted in itself.

There also seems to be no magical story behind why Robinson wore 42, other than it’s what the Dodgers gave him to wear.

In Triple-A, Robinson wore No. 10. During his days with the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues, various accounts have him wearing Nos. 5, 8 and 23.

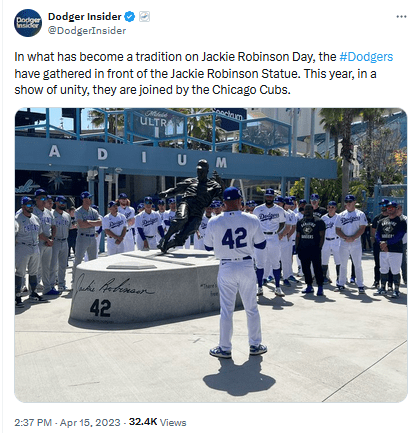

Ken Griffey Jr. is probably most responsible for making No. 42 more ubiquitous. When then–MLB Commissioner Bud Selig retired No. 42 for all of baseball on April 15, 1997 — 50 years after Robinson’s MLB debut — Griffey, then with the Seattle Mariners, asked that his uniform number be flipped from 24 to 42 for that day. It was.

By 2004, the league started an annual Jackie Robinson Day. In 2007, Griffey, then with the Cincinnati Reds, asked Selig if he could wear 42 again for the special occasion. Selig got the OK from Rachel Robinson — and the offer was made to any MLB player who wanted to make that number change as well. Then it became a thing.

We might come up with 42 reasons why Robinson didn’t become our prime focus for No. 42, but the primary reason is that No. 42 is far more acrimonious with Robinson’s Brooklyn Dodgers career. He didn’t come with the team when it moved to Los Angeles. Robinson retired in 1957 before the Dodgers could trade him to the rival Giants.

A company named PASADENA CLSC (pronounced Classic), was started in 2019 by graphic designer Dennis Robinson, the grandson of Jack’s brother, Mack, to celebrate his great uncle’s legacy as well as celebrate the community’s history. By some accounts, Robinson would not have been comfortable with this “42” branding opportunity by MLB. Especially as it seems “42” has become a selling point when put on all sorts of hats, clothes, jackets, socks … It’s easily identifiable with a man, a cause and a statement of one’s social justice beliefs. The MLB duly notes that with its own product line.

We consider Robinson’s greatest impact in Southern California sports history when he wore No. 28 playing football.

In 2017, when the Dodgers unveiled a statue honoring Robinson outside of Dodger Stadium, Vin Scully, as the master of ceremonies, told several stories about his relationship with Robinson, going back to Scully’s first year broadcasting Dodgers games in Brooklyn in 1950. Scully punctuated that speech with this “Jackie Robinson Day” celebration on April 15:

“All across the country, in every major-league ballpark, every player will be wearing 42. And what does the 42 means? It doesn’t mean that (the players) are all equal. … but the one thing they share in carrying 42 is the fact that the man who wore it gave them the one thing that no one at the time could have ever done. He gave them equality. And he gave them opportunity. Those were the two things many of those people never had to hold in their hearts when they first began to play. So, yes, 42 is a great number, it means a lot for a great man, but it is a tremendous number when you think of a man who wore it with such dignity, with such pride, and with such great discipline.”

So there’s that …

Anyone else able to explain how the number 42 seems to be somehow attached as the “Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything”?

In Douglas Adams’ late ’70s/early ’80s comedy/science fiction book series, “The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy,” No. 42 is the simple answer that comes up after a super computer called “Deep Thought” spends 7 ½ billion years of calculation pondering that the aforementioned question. Or was it a real question. The creators did not actually know what the “Ultimate Question” was, rendering the answer 42 even more confusing.

Adams, when asked, said he simply picked that answer because it was an ordinary, small number.

How so? What does it all mean? Was he a Jack Robinson fan?

Sit with that awhile and see where the universe takes you.

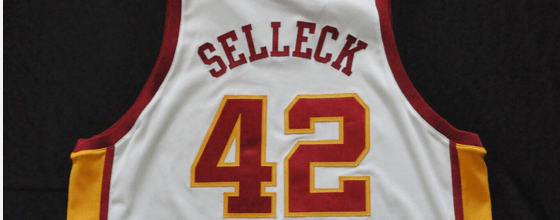

No. 42: Tom Selleck

You never know when a low dose of a early-morning TV chat show might actually clarify some urban Hollywood legend and lead to some legitimate record-keeping.

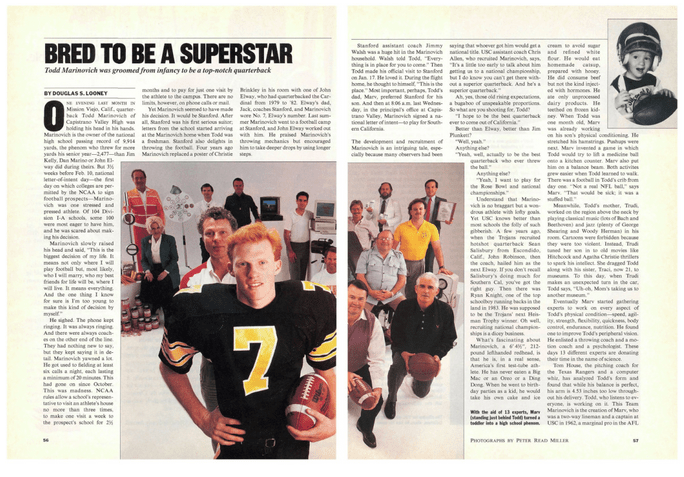

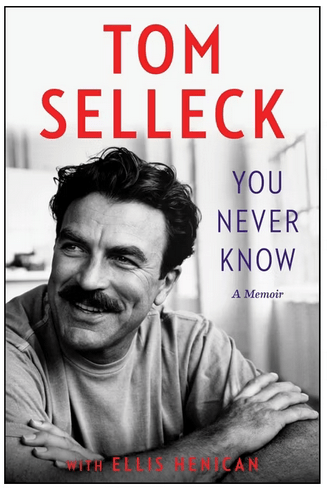

In May of 2024, Tom Selleck climbed up in the high-back chair as a guest on “Live with Kelly and Mark,” taking questions about how he went from a USC basketball player to a Hollywood actor based on his newly released memoir, “You Never Know.” The nattering ABC coffee klatch visit was also a place to get nostalgic for the end of his participation in the long-running CBS series “Blue Bloods.”

“You wanted to be — and I did not realize this — a professional athlete!?” co-host Kelly Rippa piped up as she boosted herself up in her seat.

Selleck shrugged.

“Well, it was kind of a fantasy,” he said sheepishly. “(At first) it was baseball, then I got a little burned out, and by the time I got to ‘SC, I thought it was basketball …”

“You got a scholarship, in fact!” Kelly interjected.

“No,” Selleck answered, almost apologetic. “I was a walk on. Basically my real job was riding the pine at USC … I earned a scholarship my last semester.”

Kelly’s husband and co-host Mark Consuelos finally jumped in.

“And basketball somehow led to your acting career, yes!?” he suggested.

“No …” Selleck hesitantly replied again, paused and started to chuckle.

“It says so on these cards here!” Kelly reminded him, trying to save some face.

“I was in the business school, and don’t look at my transcripts, I was not doing well,” Selleck explained. “College was way too much fun. I did get a basketball commercial for Pepsi-Cola because I could stuff a basketball with either hand. It wasn’t my acting ability.”

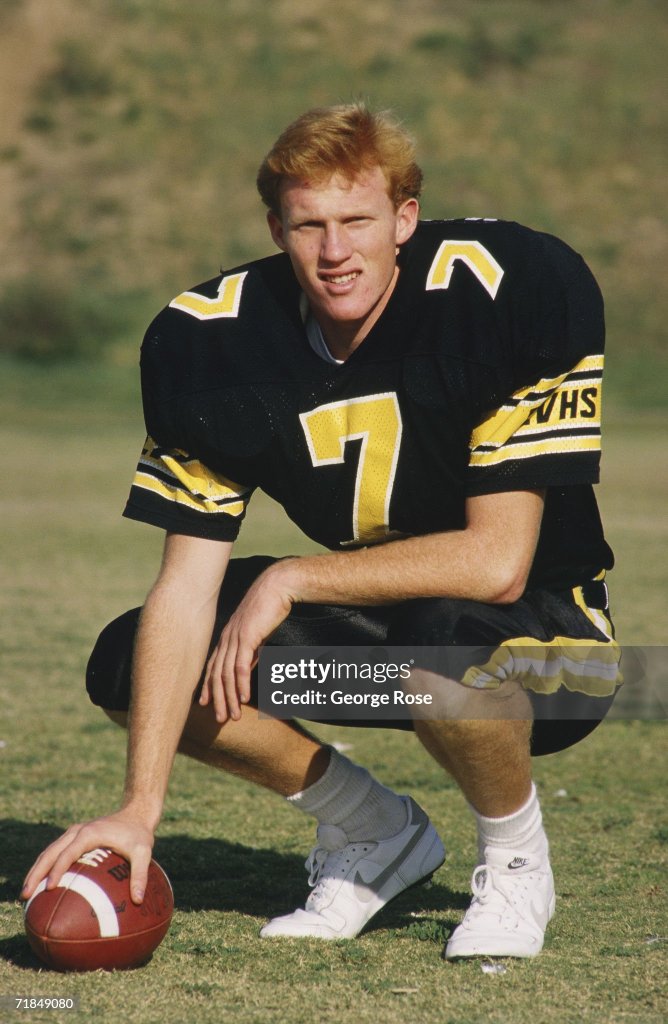

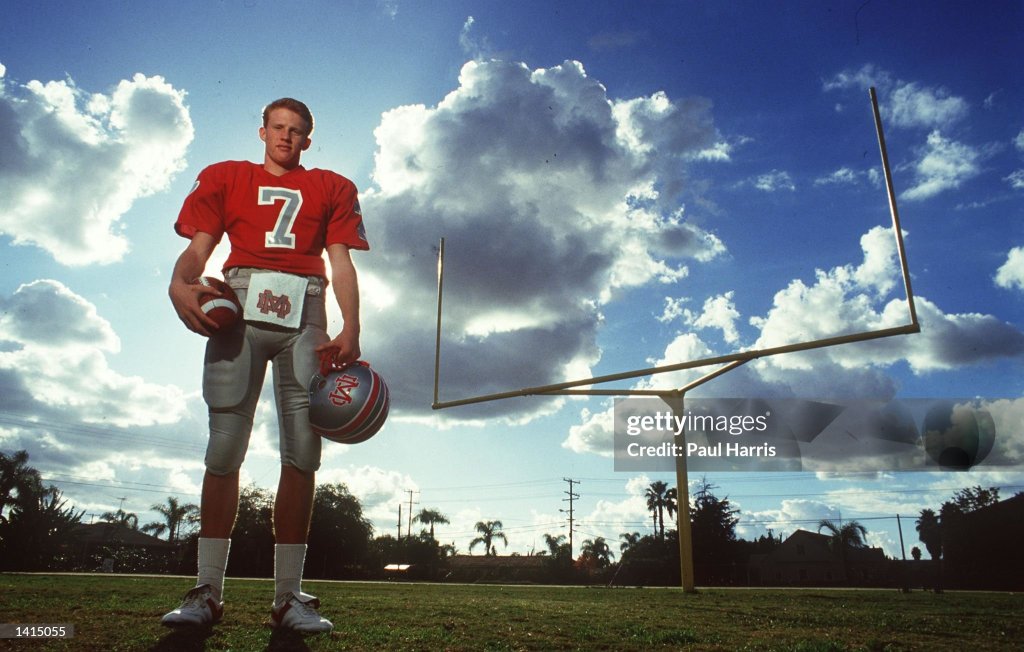

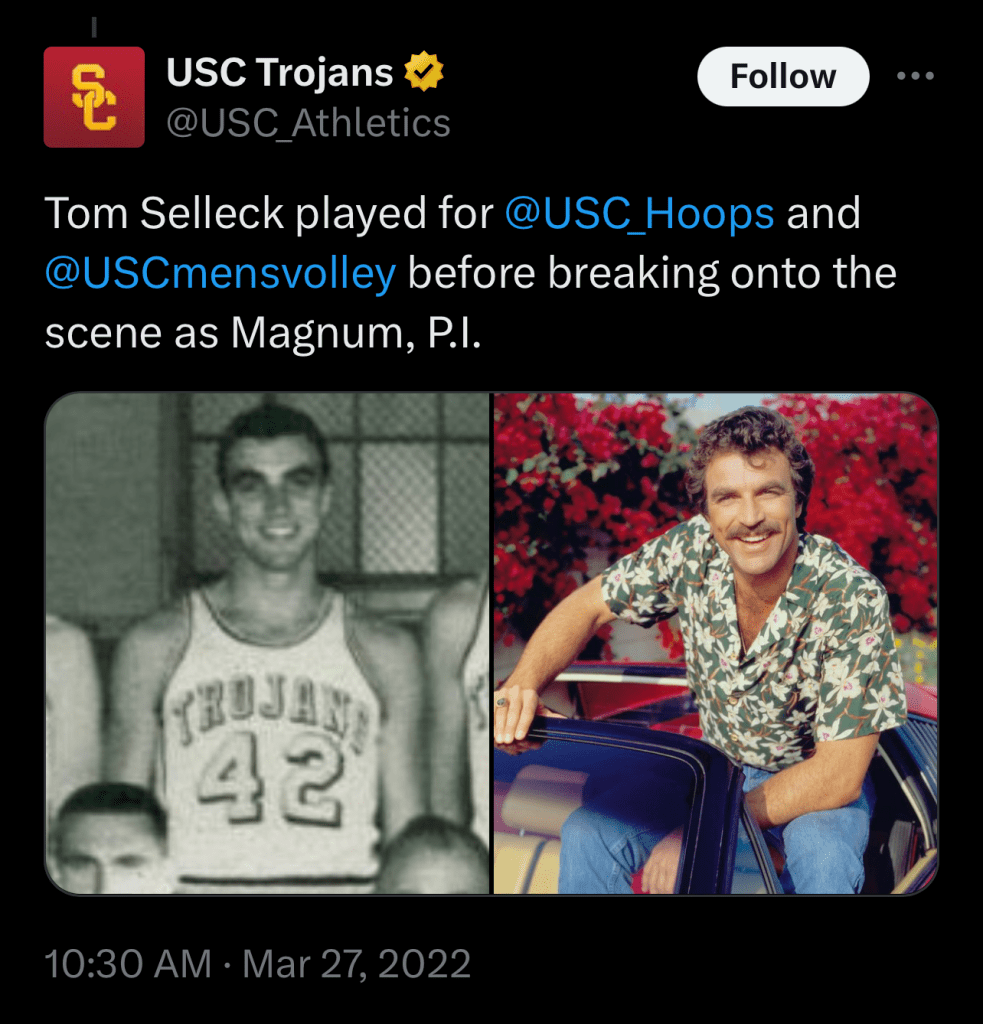

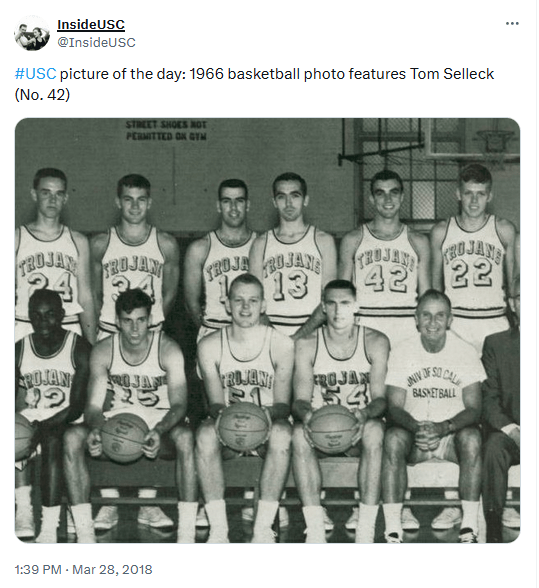

As a result, short story long, Selleck officially spent two years as a USC basketball player wearing No. 42 — it got him into 10 games, scoring a total of four points. It was a means to an end.

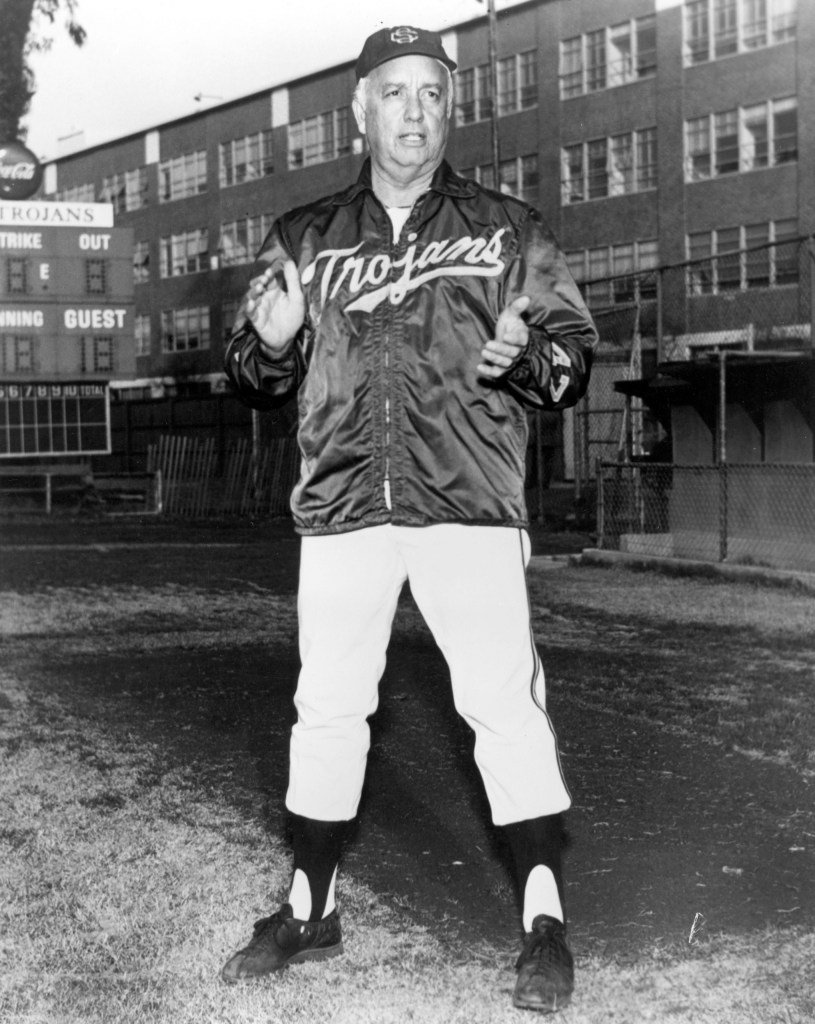

During that time, overlapping the final season USC had Forest Twogood as its head coach and the first year of Bob Boyd, two fortunate things happened for Selleck as he scratched his jock/frat boy status.

It got him two appearances on “The Dating Game,” which led to the Pepsi commercial.

And he got to act the role of Lew Alcindor during USC basketball practice.

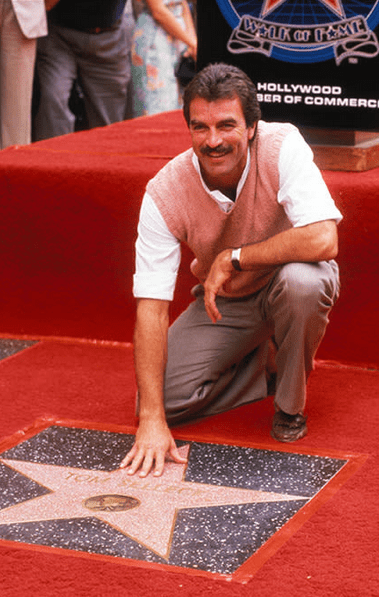

Did either directly lead to a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame?

Really, you never know.

The backstory

Tom Selleck’s somewhat Horatio Alger story has been documented by the Horatio Alger Association of Distinguished Americans website. The group honored him in 2000.

In a profile it crafted, it starts by noting Selleck was born in Detroit on Jan. 29, 1945, at a time when his father, Robert, worked in the U.S. Army as a mechanic on B-29 bombers. Detroit’s Tigers became Selleck’s favorite team, and outfielder Al Kaline his favorite player.

A carpenter by trade, Robert Selleck moved the family with more than what they could fit into the family car and, with the help of the GI bill, made a down payment on a small house in Sherman Oaks in 1949. Tom was 4.

“They lived a life of strong moral values and taught us that you are judged by your last worst act,” Tom Selleck said of his parents. “They didn’t lecture us about how to be good; they just set a good example. They walked their talk.”

Selleck took to baseball and made the All-Star team as a pitcher with the Pioneer Little League of Sherman Oaks. Or so it says when, in 1991, the Little League Museum in Williamsport, Pennsylvania added him to its Hall of Excellence.

Selleck’s draw to sports was as simple as following the lead of his older brother, by a year-and-a-half, Bob.

Bob and Tom held their own at Grant High in Van Nuys, focused on baseball and basketball. While Bob got a ride to USC to play baseball, Tom wanted that as his destination as well. After his senior of basketball, he had only a hoops scholarship offer to go to Montana State University. He turned it down.

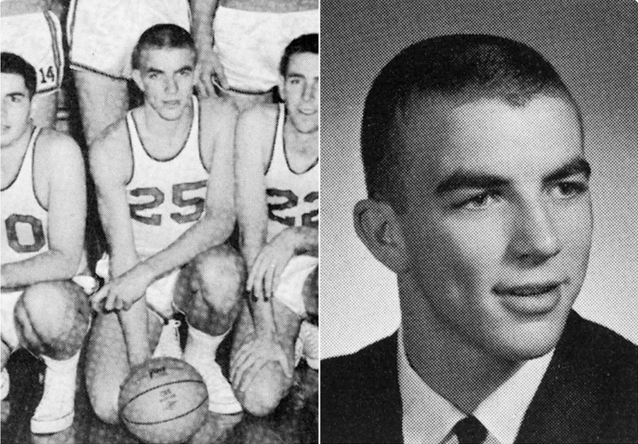

But without the grades to get into USC as a freshman, and without the financial resources, Tom Selleck went to L.A. Valley Junior College, across the street from Grant High. He could save money, live at home, play basketball and work part time at a clothing store.

And make local headlines in the sports pages.

In the Nov. 28, 1962, edition of the Valley Times, two photos of Selleck (wearing No. 25) made the cover. He scored nine points in a 61-60 loss to Citrus College.

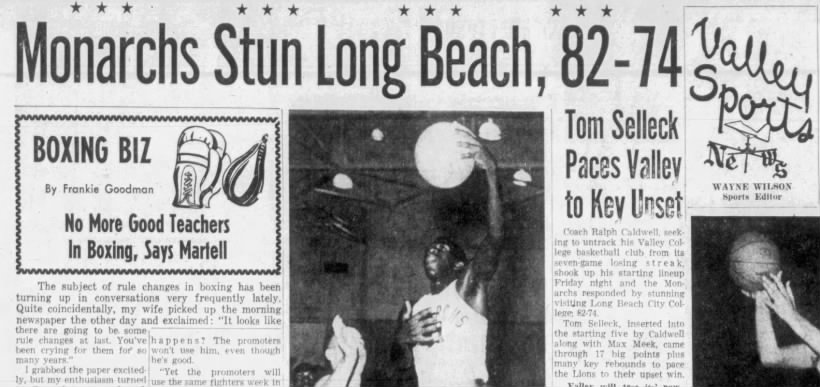

Six weeks later, in a Jan. 13, 1963 edition of the Van Nuys News and Valley Green Sheet, a story on Valley College’ 82-74 upset over Long Beach City College pushed Selleck into a deck headline. Valley ended a seven-game losing streak — maybe because Selleck was moved into the starting lineup and came up with 17 points to pace the Monarchs’ win. That team still finished 5-25.

Said Coach Ralph Caldwell: “Selleck really made the difference for us. We were looking for better ball handling and control.”

In a March 1964 edition of the Van Nuys News and Valley Green Sheet, it noted that Valley College’s 88-66 win over Bakersfield ended the season on a high note during a 14-18 average season.

“Selleck, playing in his last game for Valley, turned in the highest scoring performance of his two-year career and was a tiger on both backboards,” the story noted. “The 6-foot-3 center was second to (Leonard) McElhannon in the Valley scoring column with 19 markers. (With the game tied at 24-24), Selleck followed with two baskets in the next 16 seconds. First he hit on a jumper, then intercepted a Bakersfield pass and drove three-quarters of the court for the lay-in. That made the count 28-24 and Valley never relinquished the lead.”

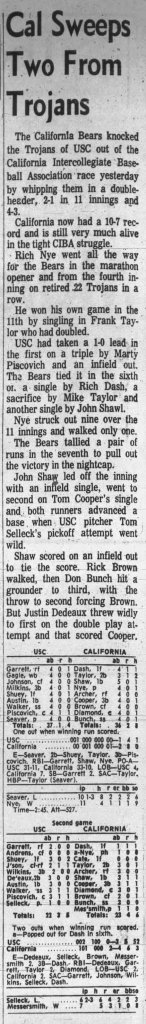

Bob Selleck, meanwhile, was on Rod Dedeaux’s USC baseball teams that won the NCAA title in 1963 and went to the College World Series in ’64.

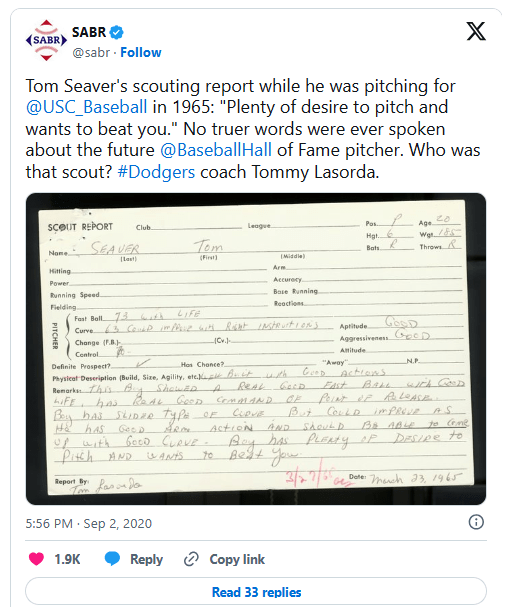

A May 9, 1965 story posted in the Oakland Tribune noted that when USC lost a double header to Cal, knocking the Trojans out of the California Intercollegiate Baseball Association title, it was Bob Selleck (not “Tom” as he was mistakenly identified) who lost the second game after throwing 6 2/3 innings (of a seven-inning scheduled contest), worsened with he made a wild pick-off throw. Cal’s winning pitcher was future Dodger and Angel Andy Messersmith, who went all seven. (In the opener, Trojan starter Tom Seaver took the 2-1 loss despite pitching 10 1/3 innings).

From there, Bob Selleck, a 6-foot-6 right-hander, ended up pitching three seasons in the Dodgers’ Single-A level of their farm system, going 11-19 with a 4.66 ERA in 63 games.

Tom Selleck would need to put in two-and-a-half years at L.A. Valley College to get his grades in order for a USC transfer. He would then need need two-and-a-half more years at USC to reach senior status. He started as a business major. The business of Hollywood seemed to make more sense.

In his book, “You Never Know,” Selleck recounted a time when he thought his USC eligibility to play basketball was in real jeopardy because of failing grades. He had dropped classes and begged teachers for passing grades just to keep him on the roster. It all caught up with him.

Selleck wrote that he made an appointment to see Dr. William Himstreet, associate dean of the USC business school. Before Selleck could talk about his grades, Himstreet said:

“I pulled your transcript, and I have to say, I was very impressed … Your transcript is on of the most remarkable records of mediocrity I have ever seen. You’ve never gotten higher than a C in your major, and sometimes worse.”

USC officials had told him pretty much the same thing when he tried to transfer the first time after two years at L.A. Valley College.

Selleck wrote that he found a class that “was supposed to be an easy A” called The History of American Theater. Class professor Robert Rivera thought Selleck would be “a good type” for commercials and recommended an agent.

“Well, I wasn’t exactly serious about it,” Selleck wrote, “but I’d heard you could make a lot of money doing a commercial. I mean, you never know …”

Meanwhile, Selleck’s fraternity brothers at Sigma Chi talked him into going onto the popular 1960s TV show, “The Dating Game.” Selleck said they even figured out how to rig it by giving cues from friends in the audience.

In a 1967 appearance, host Jim Lange honed in on Selleck’s USC hoop status by introducing him: “Standing 6-foot-4, it’s reasonable and correct to surmise Bachelor No. 2 is an outstanding varsity basketball player. He plans to enter the world of business along administrative lines. He’s from Detroit, Michigan, we’d like you to meet Tom Selleck.”

The young blonde named Madonna asks the questions on the other side of the set: “Bachelor No. 2, if you were a statue what would you be doing and what would you be called?”

Selleck: “I’d be holding a fig leaf and … I’d be called ‘Nude.’”

Naked and afraid, Selleck thought it was just as well he lost out to Bachelor No. 3 and got a record player as a parting gift.

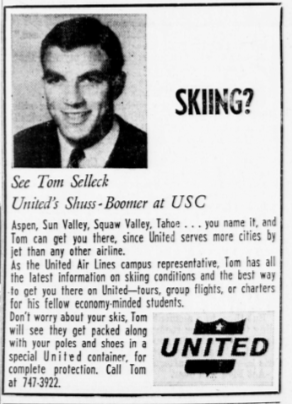

As a way to draw some income at the time, Selleck worked for United Airlines as a USC campus rep. If you saw this ad in the Daily Trojan with his handsome mug, wouldn’t you give him a call at 747-3922 and see if he could “get your piles and shoes in a special United container for complete protection” as you jetted off to Squaw Valley — a place you can’t call Squaw Valley any more and is known as Palisades Tahoe?

The story goes that Selleck’s “The Dating Game” exposure got him enough attention to lead to a Pepsi-Cola commercial, all thanks to his new commercial agent, Don Schwartz. All that it really involved was Selleck playing some basketball, pretend to dunk and enjoy the fizz in the locker room (sporting a No. 8 jersey).

Schwartz’s career plan for Selleck started by convincing both Universal Studios and 20th Century Fox Studios that each was interested in having Selleck be part of its “New Talent” programs. It’s called working the room, and as a result got Selleck an interview with each studio.

Selleck wrote at a time when he and his USC basketball teammates were sequestered from Thursday night to Sunday morning at the Chapman Park Hotel near the old Coconut Grove of the Ambassador Hotel — a way Boyd could keep the team from straying as it played games Friday and Saturday night at the L.A. Sports Arena — he had to figure out a way to rehearse a scene from “Barefoot In The Park” to perform as part of his studio auditions.

Selleck wrote in his book that after a generally OK meeting at Universal, he went to Fox and found himself in the office of Richard Zanuck, who was son of 20th Century-Fox founder Darryl Zanuck.

“You play at USC,” Zanuck asked as he scanned Selleck’s resume.

“Yessir.”

“I’m a huge UCLA fan.”

“Well, that’s too bad,” Selleck replied, saying he was trying to prove that he “was a true Trojan.”

Zanuck wasn’t pleased.

“That stall you guys did against us, that was a pretty cheap trick.”

“Whatever it takes,” Selleck said.

The backstory: USC, like any ever other team in the country at that time, needed to figure out how to with UCLA’s 7-foot-2 sophomore center Lew Alcindor, starting his three straight seasons of All-American status as a rather unstoppable force.

During that 1966-67 Athletic Association of Western Universities season, UCLA would defeat USC four times en route to a 30-0 record and start-to-finish No. 1 ranking climaxed by a national title in a 15-point win over Dayton (the tournament being just a 23-team affair at the time).

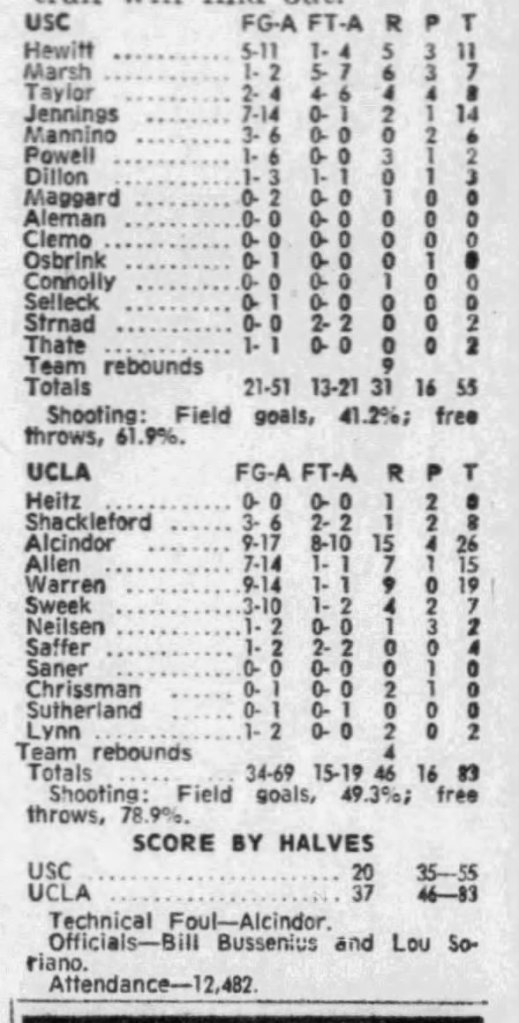

UCLA thumped USC in the Dec. 3, 1966 season opener, 105-90, as Alcindor, in his varsity debut, shattered the Bruins’ single-game record with 56 points — more than he ever scored in a high school or UCLA freshman game. Selleck wasn’t among the 13 USC players who got playing time in that contest. The teams were actually tied at 16-16 at one point.

“We don’t fear Alcindor,” Boyd said after the game, “but we have awesome respect.”

In late December, the Bruins went out to a 14-0 lead and pounded the Trojans even worse, 107-83, to win the Los Angeles Classic Tournament. Alcindor had 25 points on 8-of-11 shooting — a foul tactic by USC led him to convert 9 of 12 free throws. Selleck didn’t play among the 11 USC thrown to the wolves.

Those two meetings were at Pauley Pavilion, where UCLA would play 17 of their 26 regular-season games.

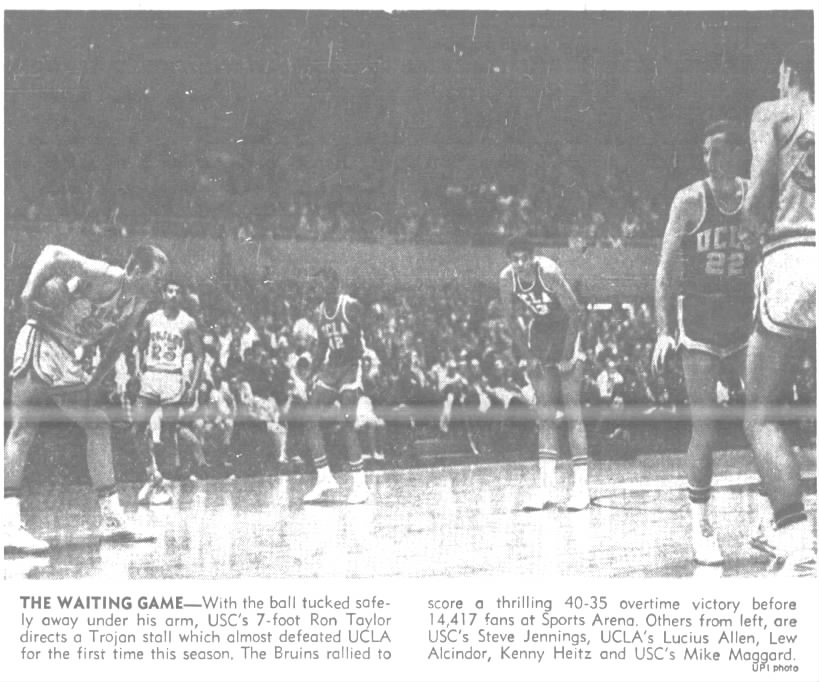

But in the February 4 conference meeting at the L.A. Sports Arena, on USC’s home court, Boyd pondered the effectiveness of a stall.

Taking advantage of no shot clock, the offense could do whatever it wanted when it had possession. Pass. Dribble. Pass. Hold it. It’s a boring game of keep away, all within the rules (and obviously since changed.)

It almost worked. USC fell behind, 7-2, a minute into the game. The Trojans went 8 1/2 minutes without shooting on one possession in the second half — and UCLA’s radio coverage on KMPC decided to go to commercials at one point in that stretch. The game was tied at 31 with two minutes left. USC milked the clock to three seconds remaining in regulation when Bill Hewitt missed a 20-footer. In overtime, UCLA pulled away for a 40-35 win as three USC players fouled out, content on holding Alcindor to 13 points and 10 rebounds. Selleck wasn’t among the seven Trojans who played that game.

UCLA fans spit on Boyd as he stood in front of the USC bench, and he needed an escort of seven police officers, guarding him from the many angry among 14,417 — most from UCLA, as USC would normally average about 2,000 a game.

(When the two teams played the final conference game on Saturday, March 11, again at Pauley Pavilion, Boyd did some stalling again, but eventually called it off, and the Trojans lost again by nearly 30 points, 83-55. Alcindor scored 26 (and also had a technical foul). Selleck’s final appearance as a Trojan was long enough for him to take one last shot. He was one of 15 USC players who got in).

Height-wise, USC had 7-foot-1 sophomore center Ron Taylor to match up against Alcindor. USC’s plan was to have Taylor go out on the perimeter when the Trojans had the ball, coaxing Alcindor out to defend him and open a lane behind him for someone else to shoot. Conversely, in USC zone defense, Taylor would front Alcindor with another Trojans forward (or two) would come in behind to double team.

Super-sub Selleck was one of the few Trojan players aside from Taylor who could replicate Alcindor’s moves for the starting lineup during USC’s practices for those UCLA meetings. Selleck told all that to Zanuck.

“Actually I ride the pine most of the time,” Selleck said. “But when we prepare a game with you guys, the players who aren’t gonna see much action run the UCLA offense against the starters. We don’t have a tall bench. So, when we’re running the UCLA offense, I am Lew Alcindor.”

Selleck noted that Zanuck “looked like a kid staring into a giant bowl of ice cream. ‘No kidding?’ he asked.

‘ “No kidding.’

Zanuck turned to his Fox assistant and said: “Okay, lets do it” with Selleck.

Now Selleck can shrug it all off.

“The whole thing is stunning when you think about it,” he explained in his book. “A kid goes on The Dating Game and, through the machinations of a clever agent, two of the biggest studios in Hollywood each think the other is interested in him. This kid, who has no real acting experience and no real desire to become an actor, ends up bullshiting with the president of 20th Century-Fox and is promptly invited into the studio’s New Talent program. And what seals the deal is college basketball. Go figure … You never know.”

Encouraged by a drama coach to pursue whatever Hollywood could offer him, Selleck dropped out of USC to become a full-time thespian-in-pursuit. Also at that time, he got a draft notice. He enlisted in the U.S. National Guard, attended Officer Candidate School, and earned the rank of sergeant.

Looking for acting gigs, Selleck moved into an apartment with brother Bob, kept doing commercials, and made six TV pilots. None were picked up.

One odd break came in the making of the 1970 Hollywood parody film “Myra Breckenridge” with Mae West and Raquel Welch. Selleck’s role was listed as “Stud.”

It led to a 1972 commercial for Safeguard that safeguarded his income for awhile. He not only looked good, but he smelled superb.

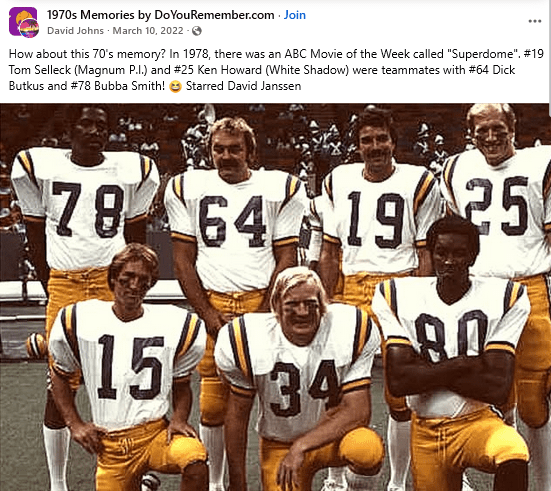

The athlete/actor combo worked for him in the 1978 ABC “Movie of the Week” drama “Superdome,” which used the Super Bowl then in New Orleans as the backdrop. NFL player such as Dick Butkus, Bubba Smith and Les Josephson were part of the cast as Selleck played Cougars quarterback Jim McCauley, wearing No. 19.

A recurring role on “The Rockford Files” in 1978 and ’79 with Jim Garner helped Selleck find a Hollywood mentor for his career. But he knew that “pretty soon I was going to reach a stage when I would either have to make it or walk away and try something else,” Selleck wrote.

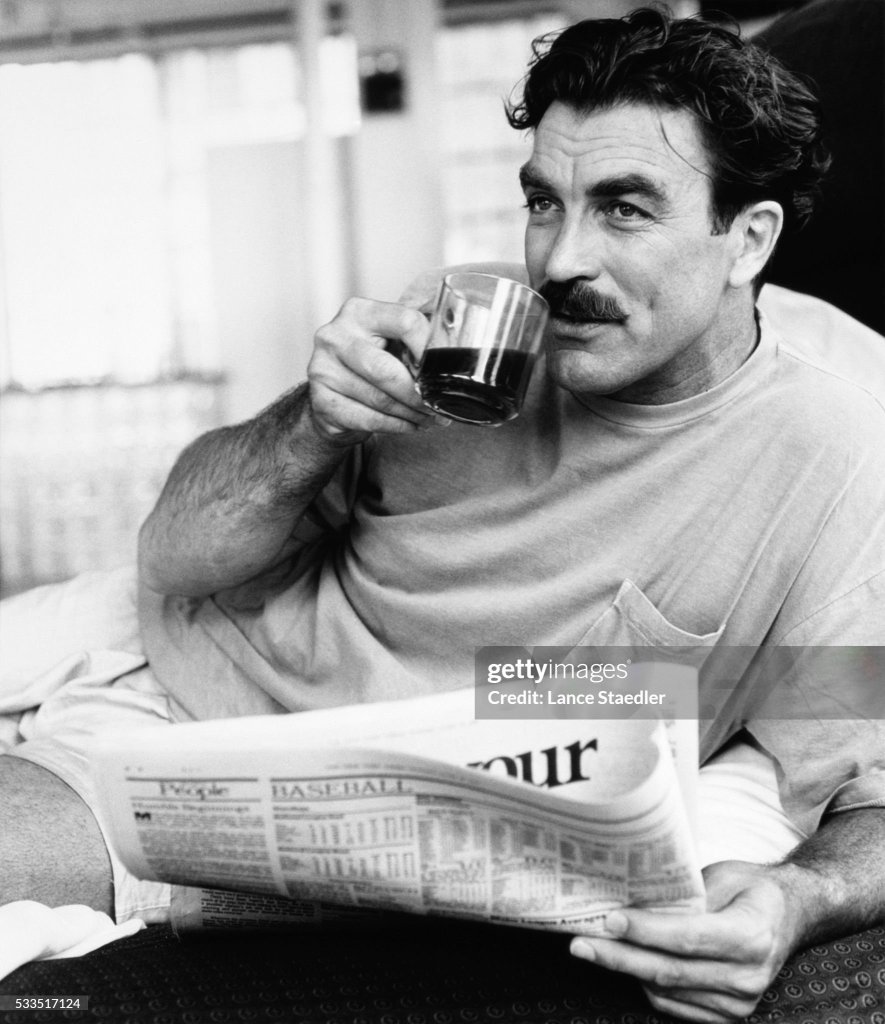

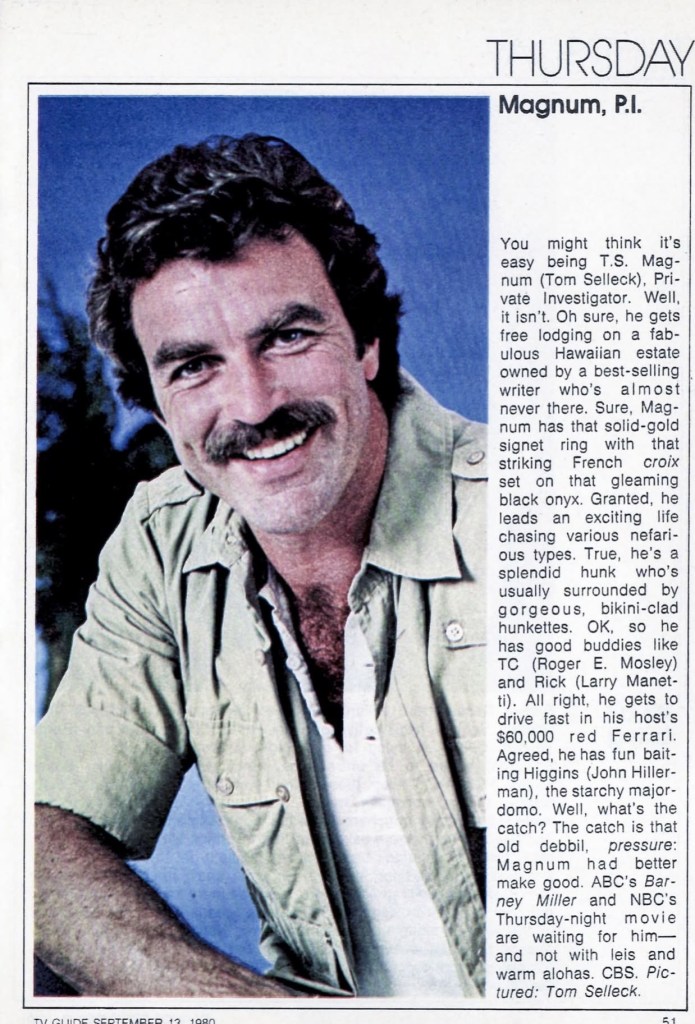

Then came the pilot for the TV series “Magnum, P.I.” Selleck played a Vietnam vet and former Navy SEAL who relocates to Hawaii and becomes a private investigator. For 158 episodes, from 1980 to 1988, Selleck became Magnum, complete with his hometown Detroit Tigers’ cap.

He almost got to be more famous in a fedora.

Selleck was said to have been on the producers’ radar to play the role of Indiana Jones for the 1981 “Raiders of the Lost Ark.” He passed the screen test by creator George Lucas and director Stephen Speilberg. Selleck was officially cast. But CBS, which just picked up the “Magnum” pilot, wouldn’t let him out of his contract as it was ramping up its series. A Hollywood actors’ strike happened right after the decision and caused production on “Magnum” to shut down for months, meaning Selleck potentially could have done both anyway. Enter Harrison Ford.

(You’d think Kelly or Mark might have jumped on that story line?)

Selleck wrote in his book that during his final season of basketball at USC in ’66-’67, coach Bob Boyd used to say: “You have to play through fatigue.” Part of that was Boyd making the team run wind sprints before they practiced shooting free throws. It became a life lesson for Selleck in Hollywood.

“Coach Boyd was a good coach, not to mention that he had the wisdom to give me a scholarship,” Selleck wrote.

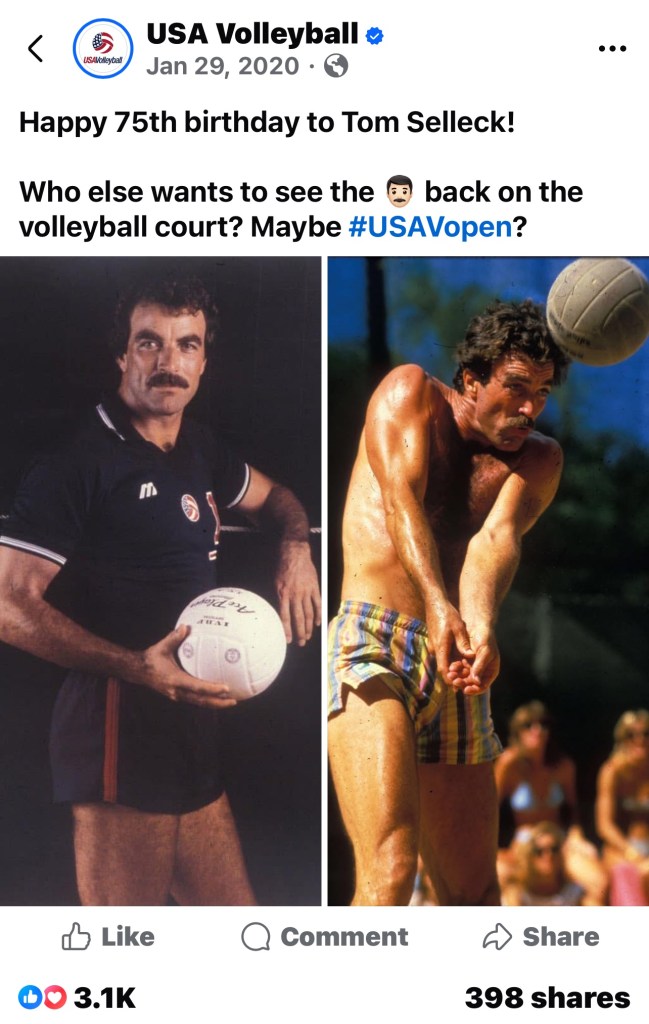

When the grind of working on “Magnum P.I.” took hold, Selleck said Boyd’s advice and even found a new sports outlet: Volleyball.

During that time filming in Hawaii, Selleck was coaxed to joined up with the AAU Outback Volleyball team, made up of former USC players. They won the 1983 AAU National Volleyball Championship against a team called The Legends of San Diego.

At the height of that fame, Selleck somehow became the honorary captain of the U.S. men’s Summer Olympics volleyball team at the Los Angeles Games in 1984. He would sign posters of him in uniform to sell for fundraising.

Somehow, some confused that Selleck played volleyball at USC. In Sports Illustrated, Selleck was called a “former Trojan spiker” watching his step son, middle blocker Kevin Shepard, compete for USC in the 1990 NCAA volleyball finals when the Trojans upset Long Beach State. The truth is, USC didn’t start its men’s volleyball program until 1970 after Selleck left.

During his “Magnum” run, Selleck’s most dream-like sports experience came when he was allowed to take batting practice with his Detroit Tigers in May of 1986 — cashing in on the “D” cap fame to fulfill a fantasy. The show’s run on CBS followed by years of reruns and earned Selleck an Emmy for Outstanding Lead Actor in a Drama Series in 1984 — the year the Tigers won the World Series.

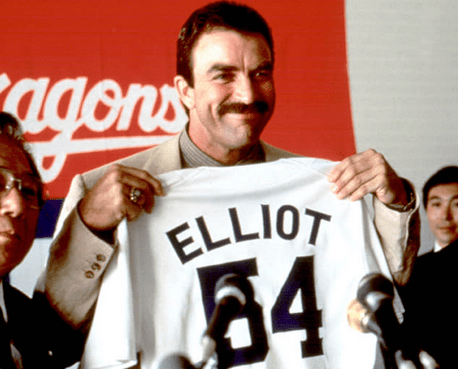

By 1992, Selleck had the title role of Jack Elliott in “Mr. Baseball” and got to perform before fans at Yankee Stadium. As an aging New York Yankees first baseman about to be replaced by upstart Ricky Davis (played by Frank Thomas), Elliott went to play for the Japanese Central League’s Chunichi Dragons.Sellect got to wear what looked like a cross between the Old-English Detroit “D” an a cheesy Dodgers Little League cap. The film tried to catch the wave of baseball films in 1989 that included the success of “Major League.”

Selleck told writers during the press junkets this all reminded him of when he was a kid and dreamed of playing big-league baseball.

To prepare for the role, and promote it as well, Selleck went to spring training with the Tigers and, thanks to manager Sparky Anderson, got to wear No. 14 and was put into a game as an eighth-inning pinch hitter against Cincinnati’s Tim Layana, the former Loyola Marymount University standout. Layana struck him out on a knuckle curve.

It was written somewhere that, once upon a time, Selleck was told by Hall of Famer Mickey Mantle that he had “major league potential.” Selleck had given up on baseball long before going to USC.

Selleck wrote in his book that after his first year of basketball at L.A. Valley College, “it just naturally followed that I would play baseball next. I loved baseball. I’d played organized baseball since I was nine years old. Bob and I would play catch on the driveway of our house on Peach Grove Street in Sherman Oaks. We always hoped dad would get home early and join us. I’d played Little League, Babe Ruth League and high school baseball. But now that I was in junior college, I didn’t go out for the baseball team. I think I was a little burned out. Well, that’s the reason I gave myself.”

Selleck recounts that he was 6-foot-1 during his senior year at Grant High and “I don’t think my body caught up to my baseball skills. That’s a fancy way to say I wasn’t a starter my senior year. At the same time, I was excelling in basketball as a starter and team captain. When I got to Valley, I was 6-foot-3 and still growing and played forward. For most of my baseball playing days, I had been one of the best players on the team. Now I wasn’t. I had lost confidence and didn’t choose to fight though that adversity. I have spoken about regret. That is a big one for me, to this day.”

As Selleck showed up regularly for the Dodgers’ Hollywood Stars night promotions, he again got do a baseball related movie in 2023. An NBC made-for-TV comedy, “Touch ‘Em All McCall,” let Selleck to play a former baseball player who came back to his hometown in Oregon to coach a farm team. At that time, Selleck landed the job as New York police captain Frank Reagan for 14 seasons on the CBS TV series “Blue Bloods,” which ended in 2024.

” ‘Magnum’ changed my life for the better and worse,” he said. “There are huge consequences to being a public person. I have a typical American success story. My life has had its challenges. Certainly, nothing was handed to me. But with hard work and perseverance, I was able to achieve my dream.”

For better or worse, the people in Detroit haven’t let the “Magnum, P.I.” connection disappear.

In August of 2025, 80-year-old Selleck made a surprise appearance at Tiger Stadium to be part of its now-annual “Magnum, P.I. Day” event. More than 700 fans wore Tigers hats with their red Hawaiian shirts, khaki shorts and aviator sunglasses — some with mustaches, real and fake — to honor Selleck as well as bring awareness for the Brain Injury Association of Michigan (BIAMI).

From an athletic perspective, Selleck might be worthy of comparison to another Detroit-turned-Hollywood hero with a scruffy face and hard-nosed demeanor.

“Kirk Gibson had the life Selleck once dreamed of,” wrote Matt Zemek for USA Todays Trojan Wire.

Maybe. Then again, we may never know.

Who else wore No. 42 in SoCal sports history?

Make a case for:

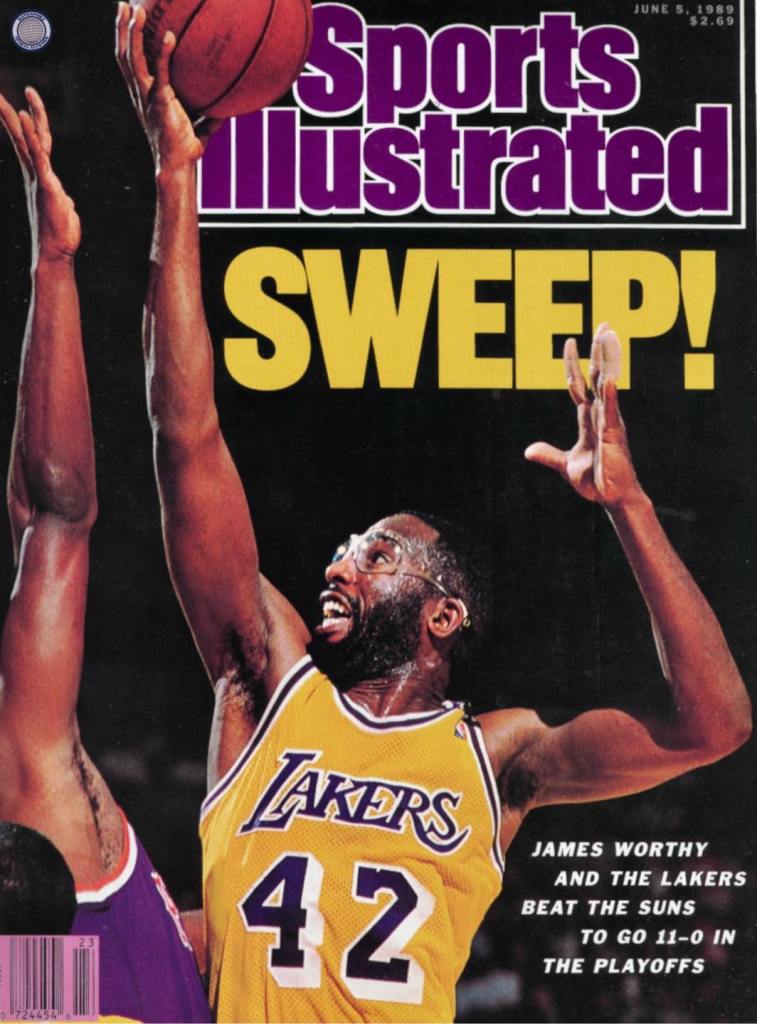

James Worthy, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1982-83 to 1993-94):

Best known: The player that broadcaster Chick Hearn called “Big Game James” was a seven-time NBA All-Star, twice All-NBA first team and voted the NBA Finals MVP in 1988 when he put up 36 points, 16 rebounds and 10 assists in the Game 7 win). The first overall pick of the 1982 draft out of North Carolina after helping the Tar Heels to the ’82 NCAA title as the tournament’s Most Outstanding Player, Worthy played all 12 of his NBA seasons with the Lakers, winning three championships. His No. 42 was retired by the team with his induction into the Basketball Hall of Fame in 2003, worthy of him being included on the NBA’s 50th and 75th anniversary teams.

Not always remembered: Back in the day, when NBA teams casually threw around draft picks like tarot cards, the Cleveland Cavaliers became the team to gang up on. The league finally had to stop them from trading away their future. Before that could happen, Cleveland, again having the worst record in the league in 1981, with the help of a coin toss, gave the Lakers — one year removed from a title — the No. 1 overall pick in the 1983 Draft. That was included in a trade where Butch Lee was sent to L.A. as well in exchange for a Lakers’ first-round pick plus forward Don Ford. The Lakers used it to pick James Worthy. Over Dominique Wilkins.

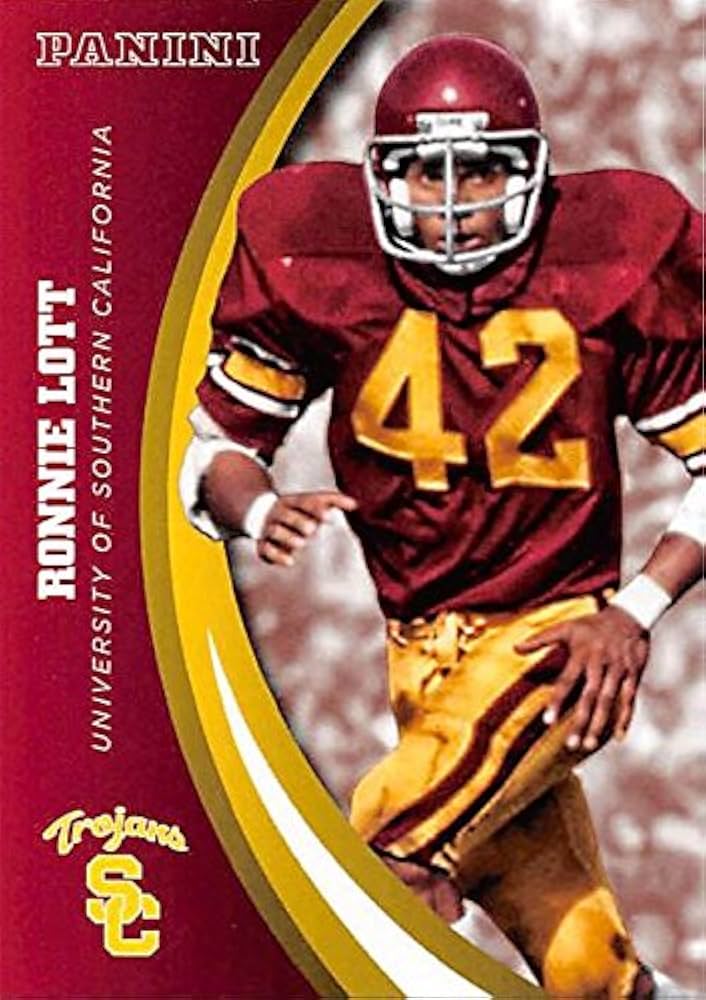

Ronnie Lott, USC football defensive back (1977 to 1980); Los Angeles Raiders strong safety (1991 to 1992):

Best known: In 2025, when the Associated Press recognized the first 100 years of its All-American Award for college football, Ronnie Lott was the only one from USC (or UCLA for that matter) who made it onto the first team of 25 players, based solely on their career in college. Lott’s eight interceptions for 166 return yards during his senior season were tops in the NCAA and earned him All-American status — the only year he was honored. Lott was voted into the USC Athletic Hall of Fame in 1995, the College Football Hall of Fame in 2002, and the Pac-12 Hall of Honor in 2019 as well as the Defensive Player of the Century on the Pac-12 All-Century team of 2015.

In 2020, when ESPN did its list of the 150 greatest college football players in the game’s first 150 years, Lott was ranked No. 58 with this writeup for a career that included 14 interceptions, 10 fumble recoveries and 250 tackles: The Trojans recruited Lott and 1981 Heisman Trophy winner Marcus Allen to play safety or running back. USC coach John Robinson thought Lott was the better tackler, so he ended up in the Trojans’ secondary, where he became one of the most feared hitters in the sport’s history. As a sophomore in 1978, Lott helped the Trojans go 12-1 and win a share of a national title. USC went 11-0-1 and was ranked No. 2 the next season. Lott was a unanimous All-American in 1980 and later won four Super Bowl championships with the San Francisco 49ers. The Lott IMPACT Trophy is given to the sport’s impact defensive player each season. In 2020, when the New York Times did a list of the “best players to wear every jersey number in college football history,” Lott was assigned No. 42.

Lott’s 14-year NFL career included 10 Pro Bowls, including one with the Los Angeles Raiders in 1992 at age 32, as a strong safety, where he was AP first-team and fourth in the AP Defensive Player of the Year. He was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2000.

Not well remembered: Lott, who played basketball as well as a freshman at USC, came out of Eisenhower High in Rialto wanting to go to UCLA. In Bruce Feldman’s 2020 oral history of the 1979 USC football team written for the New York Times, Lott said his goal was to play basketball and football at UCLA, but football coach Terry Donahue not only was against that, but he told Lott that he didn’t play freshman. “I came home and told my dad. I talked to (USC) Coach (John) Robinson, ‘Would you play freshmen?’ He said, ‘This is about competition. If you can compete, we’ll give you a shot.’ Sometimes in life, somebody can say a couple of words and those words really resonate with you and those words become the inspiration of your journey.” As it turned out, Donahue played another standout defensive back, Kenny Easley, as a freshman that same year of 1977 when both Easley and Lott entered college. Robinson had a 5-1 record in head-to-head matchups against Donahue and UCLA from 1976 through 1981. The San Francisco 49ers took Lott with the eighth-overall pick in the 1981 NFL Draft, four spots after Seattle took Easley.

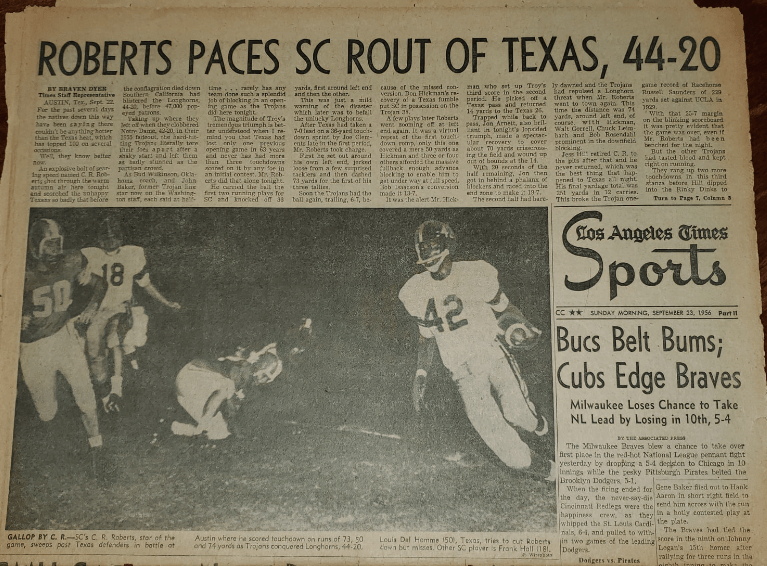

CR Roberts, USC football tailback (1955 to 1956):

Best known: Before the landmark USC-Alabama college football game that gave Sam Cunningham notoriety in 1970, CR Roberts was the most notable Black player to compete in a segregated state of Texas. In the 1956 opener, Roberts set a Trojans’ single-game rushing record with 251 yards on just 12 carries, scoring TDs on runs of 73, 50 and 74 yards, in a 44-20 win in Austin, Tex., against the Texas Longhorns. The Trojans’ coaching staff took Roberts out of the game after his third touchdown in the third quarter to protect him. A United Press International wire service report on the game called Roberts “the sensational Negro fullback.” Few, if any, news accounts made note of the societal impact of the contest. “I was upset that they didn’t want me down there,” Roberts said in a 2015 USC online article for Black History Month. “Damn right, I had something to prove to them.”

Not well known: The 1953 California state player of the year at Oceanside High near San Diego, Roberts led the Pacific Coast Conference with 775 yards on 120 carries in his final year — he also had 67 tackles and six pass deflections on defense. Although Roberts competed on the 1957 USC track team as a 100-yard sprinter and long jumper, his senior football season was wiped out as he and seven other players were declared ineligible for accepting “excessive undercover financial aid.” That led Roberts to join the Canadian Football League before going to the NFL and logging four seasons with the San Francisco 49ers. Roberts died in Norwalk at 87 in 2023.

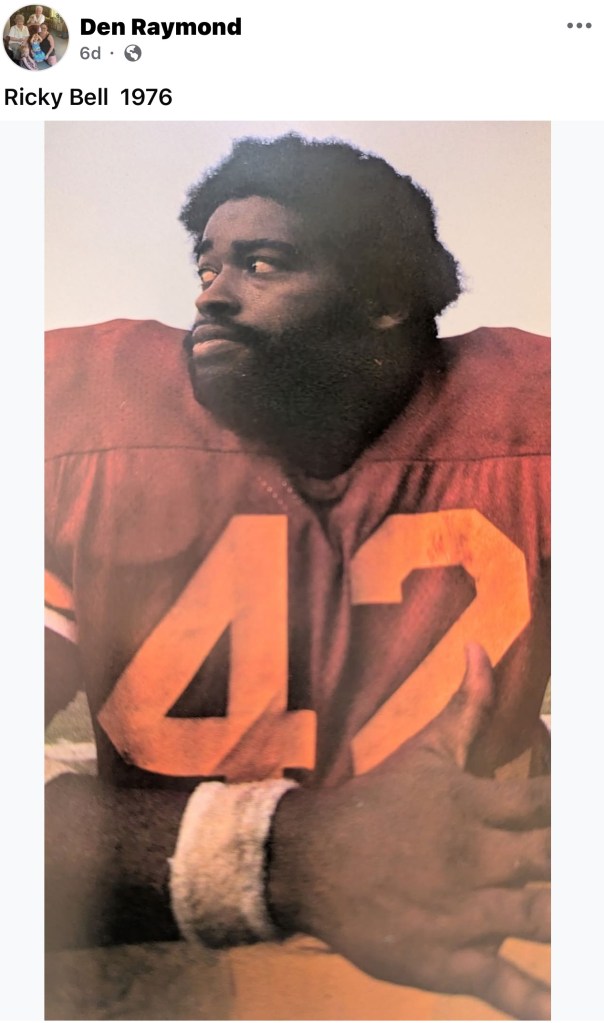

Ricky Bell, USC football tailback (1974 to 1976):

Best known: A member of the Trojans’ 1972 national title team as a sophomore where he was a 6-foot-2, 220-pound linebacker converted to fullback to block for tailback Anthony Davis, Bell was third in the Heisman Trophy balloting as a junior when he led the nation in rushing with 1,875 yards.

He finished second in the Heisman the next year as a senior when he set a Trojan school record with 347 yards rushing on 51 carries against Washington State at the Seattle Kingdome in a 23-14 win. The two-time unanimous All-American pounded out 3,553 yards rushing and 28 touchdowns in three seasons, averaging 107.7 yards per game over 33 games in his career. Bell (1,417 yards, 14 TDs) may have been second to Pitt’s Tony Dorsett (1,948 yards, 21 TDs) in the ’73 Heisman voting, but he was the No. 1 overall choice in the 1977 NFL Draft by Tampa Bay, at the recommendation of his former USC coach, John McKay. (Dorsett went second overall to Dallas). Bell signed a lucrative five-year, $1.2 million deal and in 1979 helped push the Bucs to the NFC title game against the Los Angeles Rams. He died in 1984, at age 29, of heart failure from dermatomyostis and posthumously was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 2003.

Not well remembered: A movie on his life, “A Triumph of the Heart: The Ricky Bell Story” starring Mario Van Peebles and including Marcus Allen and Charles White, came out in 1991.

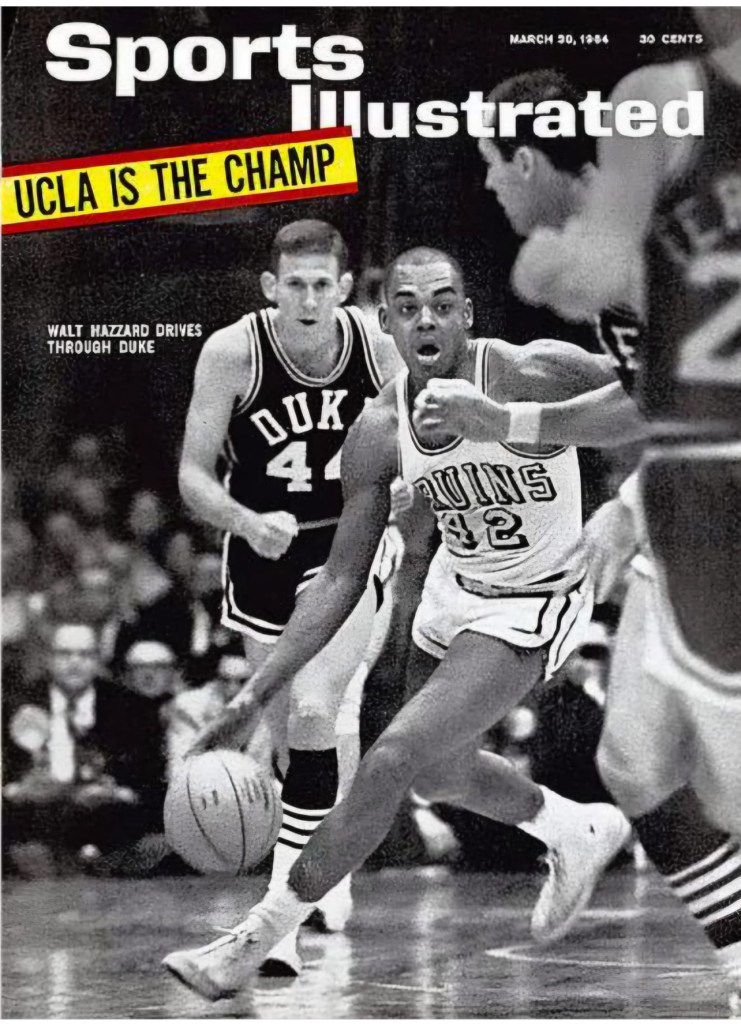

Walt Hazzard, UCLA basketball guard (1961-62 to 1963-64), Los Angeles Lakers guard (1964-65 to 1966-67):

Best known: The NCAA Tournament MVP on John Wooden’s first championship squad in 1964, Hazzard was first-team All-American as a senior, averaging 18.6 points. The first-round (No. 5 overall) pick of the Los Angeles Lakers in 1964, Hazzard, who changed his name to Mahdi Abdul-Rahman, didn’t become an All-Star pick until he was selected by the expansion Seattle SuperSonics in ’67-’68. Hazzard returned to coach UCLA’s basketball team for four seasons, going 77-47 and winning the 1985 NIT and the 1987 Pac-10 Conference title.

Not well remembered: Until UCLA decided to retire No. 42 for its entire athletic team uniforms in 2014, Hazzard had been the only athlete to official have No. 42 retired at the school for him in 1996.

Don MacLean, UCLA basketball center (1988-89 to 1991-92):

Best known: The all-time leading scorer in Pac-10 history with 2,608 points (a career 20.5 average) to go with 992 rebounds (a 7.8 average), MacLean came out as a heralded recruit out of Simi Valley High, where he led his team to the CIF-Southern Section title (and he was wearing No. 24). He set school season and career records in scoring (31.5 for a season; 26.3 for a career) as well as career rebounds (1,120) as his team won three league titles. At UCLA, he set a record for most rebounds as a freshman (231). When he was finished, he not only scored the most points, but he had the most field-goal attempts (1,776), most career 20-point games (68) and most games in double figures (123). He is tied with Lew Alcindor for most field goals (943). He led the team in scoring three times, twice in rebounding, and twice in field goal percentage. MacLean was inducted into the UCLA Athletics Hall of Fame in 2002. He never wore No. 42 in his nine-year NBA career.

Not well remembered: McLean led the Bruins in free-throw percentage all four seasons, including 1991-92 when he made 92.1 percent to lead the nation.

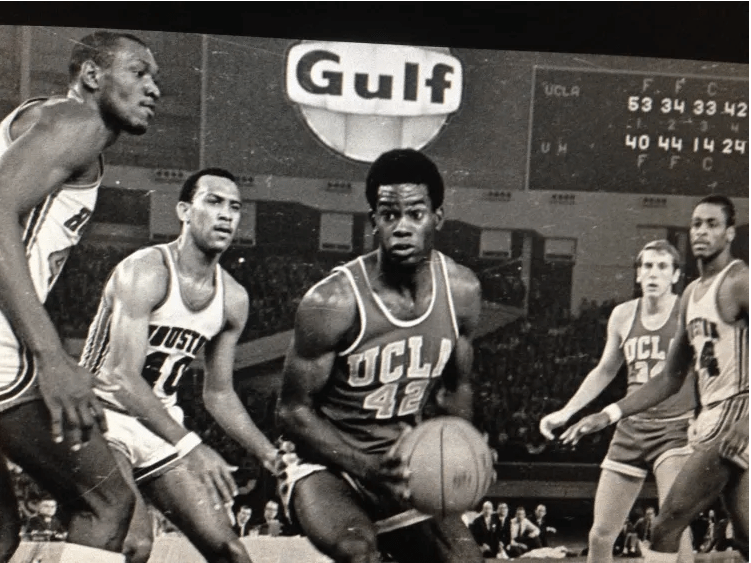

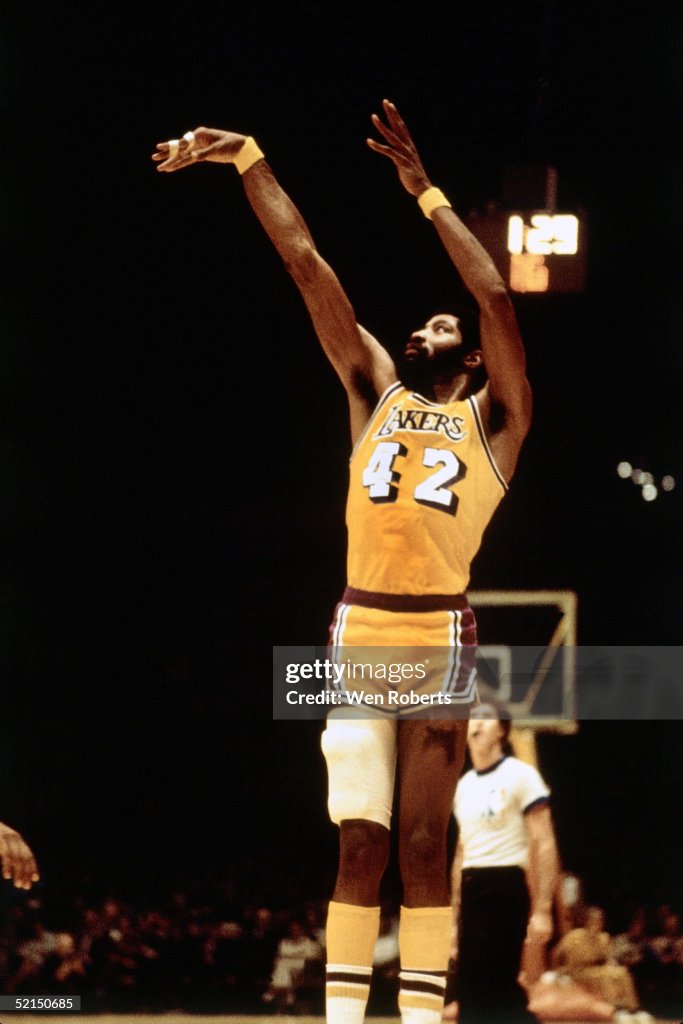

Lucius Allen, UCLA basketball guard (1966-67 to 1967-68), Los Angeles Lakers guard (1974-75 to 1976-77):

Best known: An All-American guard on two NCAA title teams for the Bruins as a sophomore and junior, averaging 15 points a game both seasons as the Bruins went 59-1, Allen was a facilitator for teammate to Lew Alcindor. The third-overall pick by Seattle in the 1969 NBA Draft, Allen also played in Milwaukee with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, was traded to the Lakers in 1974.

They united again for the ’76 and ’77 seasons in L.A., swept by eventual champion Portland in the Western Conference Finals. Allen was inducted into the UCLA Athletics Hall of Fame in 2000.

Not well remembered: Who scored the very first points ever at Pauley Pavilion? Allen, as a freshman, during the annual Freshman Team vs. Varsity Team in 1965. That was the game where Allen, and Lew Alcindor, beat the varsity 75-60, and Allen averaged 22.5 points a game before he was varsity eligible.

There was also the incident in 1968 where Allen’s UCLA career almost went up in smoke.

Kevin Love, UCLA basketball center (2007-08):

Best known: The 6-foot-10 center born in Santa Monica when his father, Stan, was playing for the Lakers, grew up in Lake Oswego, Oregon. Love was one-and-done at UCLA after an All-American season that saw him average 17.5 points and 10.6 rebounds a game for Ben Howland’s team that won the Pac-10 and finished No. 3 in the AP poll at 35-4.

Not well known: While No. 42 was already retired at UCLA for Walt Hazzard, he allowed it to be activated for Love, who us the reason why he coveted the number: “Growing up I always loved the number because my dad (Stan) was best friends with Connie Hawkins when he played on the Lakers (in the mid-’70s). I have been wearing the number as early as middle school and continued to wear it throughout high school. When it comes to UCLA, the number has a significant meaning. When I was in New Orleans this summer for a camp, I met Walt’s son, Rasheed Hazzard. In a total coincidence, Rasheed wound up being the coach of my team. I got to hang out with him and play some pickup games and developed a good friendship with him. He told me that he didn’t know what to expect when he initially met me, but afterwards told me that he would be honored if I could wear his dad’s number. Mr. Hazzard is the best for letting me wear it, I can’t thank him enough and I feel truly honored. I’ll wear it with pride.”

Connie Hawkins, Los Angeles Lakers forward (1973-74 to 1974-75):

Best known: Hawkins wore No. 42 his entire pro career — four years with the Harlem Globetrotters, a year in the American Basketball League, another three in the American Basketball Association, 10 years in the NBA, and two of his last three seasons as a Laker. Hawkins gave Los Angeles basketball fans a brief look at his remarkable talents of the Brooklyn playground legend that ended with a Basketball Hall of Fame induction in 1992, as he was often referenced as the player who did things with the basketball that were later and better known by the likes of Julius Erving, Elgin Baylor and Michael Jordan. Hawkins’ life involving gambling scandals, NBA blacklists and all his legal battles are told in the 1972 book, “Foul” by David Wolff.

Not well remembered: Hawkins was traded to the Lakers from Phoenix just a few weeks into the 1973-74 season and tied with Gail Goodrich for the team lead in assists at 5.9 a game and led the team in steals and blocks per game.

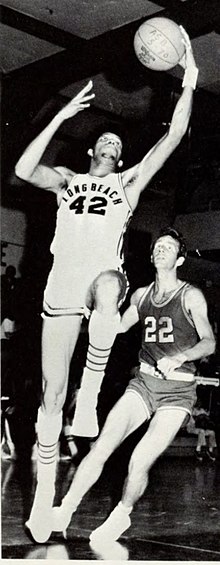

Ed Ratleff, Long Beach State basketball guard (1970-71 to 1972-73):

Best known: The two-time All-American and twice PCAA Player of the Year for Jerry Tarkanian’s 49ers had a career average (and program record) of 21.4 points a game in three seasons covering 85 games, including a single-game best of 45 points. Ratleff was also picked for the 1972 U.S. Olympic basketball team — famous for refusing to receive the silver medal after losing the title game to the Soviet Union in a controversial ending. The No. 6 pick overall by Houston in the 1973 NBA Draft, Ratleff played five seasons.

Not well remembered: Inducted into the College Basketball Hall of Fame in 2015, Ratleff’s No. 42 was retired by Long Beach State in 1973 — a situation that came to light in 1990 when the school allowed freshman Adam Henderson to wear it. Ratleff’s No. 42 was then officially re-retired in 1991.

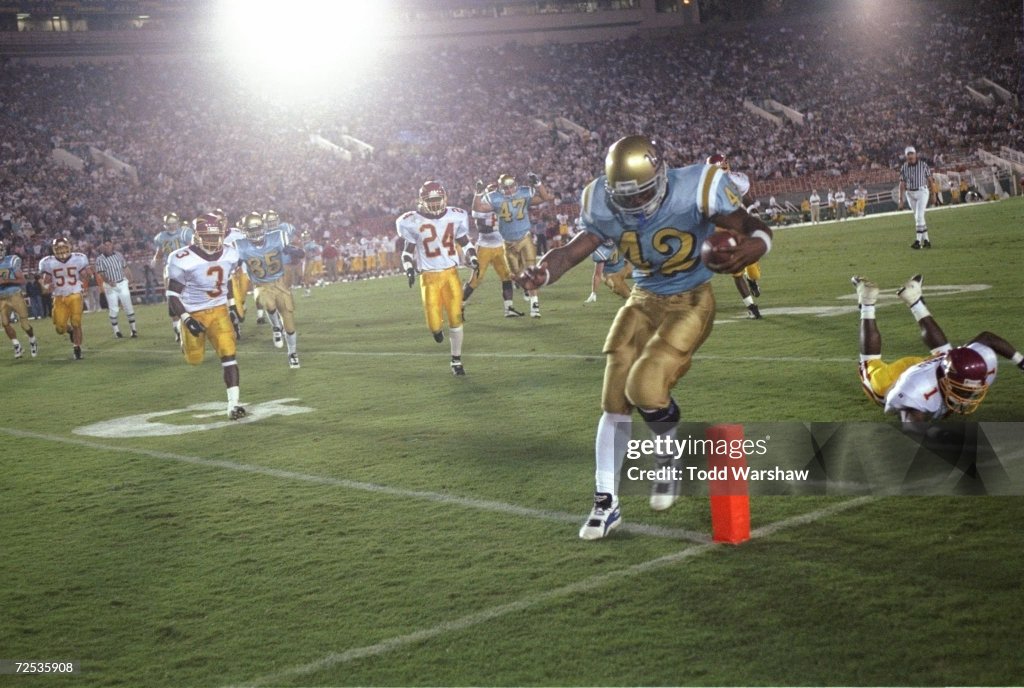

Skip Hicks, UCLA football running back (1993 to 1997):

Best known: The Bruins’ program record-holder in career touchdowns (55) also piled up the msot TDs in a season for the program — 26 in ’77, when he was first-team All-American and All-Pac-10, collecting 1,282 yards rushing and seven 100-yard rushing games. His TD marks were also conference records at the time. His 3,140 yards amassed over five seasons and 330 points are Top 10 in the program. In 1993, he became the first UCLA true freshman to lead UCLA in rushing (563 yards) and also tied for the team lead in rushing touchdowns with five. A 2019 inductee into the UCLA Athletic Hall of Fame,

Not well remembered: Hicks is the only Bruin in history to record more than 100 yards rushing and 100 yards receiving in the same game — a 39-28 win at Cal where he had 146 yards rushing and three rushing touchdowns plus 113 receiving yards on four catches and a TD reception of 63 yards in the fourth quarter.

Have you heard these stories:

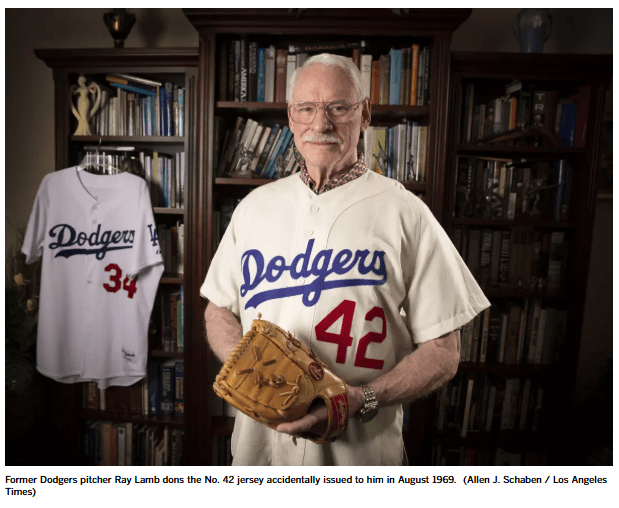

Ray Lamb, Los Angeles Dodgers pitcher (1969 to 1970):

Call him the Sacrificial Lamb. Born in Glendale and a 40th-round pick by the Dodgers out of USC, the right-handed swing-man pitcher has the odd distinction of wearing two numbers in his only two seasons with Los Angeles that the franchise would eventually retire for someone else. As a 24-year-old rookie called up in August of 1969, appearing in just 10 games, Lamb was given No. 42 — which he wore with the Trojans. The team realized it needed to take it out of circulation for Jackie Robinson to honor him in the coming years. As a result, Lamb’s second season (when he posted a 6-1 mark in 35 games) saw him wear No. 34 — to be eventually hung up for Fernando Valenzuela.

Erik Affholter, USC football receiver (1985 to 1988):

His initial claim to fame was recording the longest field goal in a game on any level — 64 yards, done as a 16-year-old at Oak Park High in Agoura against Carpinteria. The ball hit the left upright and dropped over the crossbar to eclipsed the high school record of 62 yards set in 1929 by Kelly Imhoff of Kent, Wash. And Oak Park still lost the game. In 1983, he made USA Today’s All-USC high school football team, as well as All-CIF and the Los Angeles Times’ running back of the year, while he also played receiver, linebacker and did all the kicking. At USC, Affholter is best remembered for making a juggling 33-yard touchdown catch as he was falling out of bounds in the end zone (with no replay at the time) to finish a 17-13 upset over No. 5 UCLA (9-2) on Nov. 21, 1987, sending the unranked Trojans (8-3) to the 1988 Rose Bowl. He led USC with 68 catches for 952 yards and eight touchdowns as a senior and had the school record for most receptions in a season, and in a career (123).

Mark McGwire, USC baseball first baseman/pitcher (1982 to 1984): Out of Damien High in La Verne, McGwire had 32 homers and 80 RBIs as a junior for the Trojans in 67 games, hitting .387 with a 1.361 OPS. That earned him Pac-10 Player of the Year, All-American status and a Golden Spikes Award finalist. His 54 career homers also set a USC record. But he also posted a 7-5 record and 2.93 ERA as a pitcher. After winning a silver medal with Team USA in the 1984 Summer Olympics, he was a first-round pick (No. 10 overall) by Oakland. He was inducted into the USC Athletic Hall of Fame in 1999, where, as his bio notes, he passed Babe Ruth and Roger Maris with the all-time single-season MLB home run record of 70 while with St. Louis in 1998.

We also have:

Dave Elmendorf, Los Angeles Rams safety (1971 to 1979)

Mo Vaughn, Anaheim Angels first baseman (1999 to 2001)

Elton Brand, Los Angeles Clippers forward (2001-02 to 2007-08)

Anyone else worth nominating?