This is the latest post for an ongoing media project — SoCal Sports History 101: The Prime Numbers from 00 to 99 that Uniformly, Uniquely and Unapologetically Reveal The Narrative of Our Region’s Athletic Heritage. Pick a number and highlight an athlete — person, place or thing — most obviously connected to it by fame and fortune, someone who isn’t so obvious, and then take a deeper dive into the most interesting story tied to it. It’s a combination of star power, achievement, longevity, notoriety, and, above all, what makes that athlete so Southern California. Quirkiness factors in. And it should open itself to more discussion and debate — which is what sports is best at doing.

The most obvious choices for No. 94:

= Kenechi Udeze, USC football

= Paul Bergmann, UCLA football

= Mateen Bhaghani, UCLA football

The not-so-obvious choices for No. 94:

= Terry Crews, Los Angeles Rams

The most interesting story for No. 94:

Don Yi, Korean language interpreter for Chan Ho Park (1994)

Southern California map pinpoints:

Lakewood, Glendale, Los Angeles (Dodger Stadium)

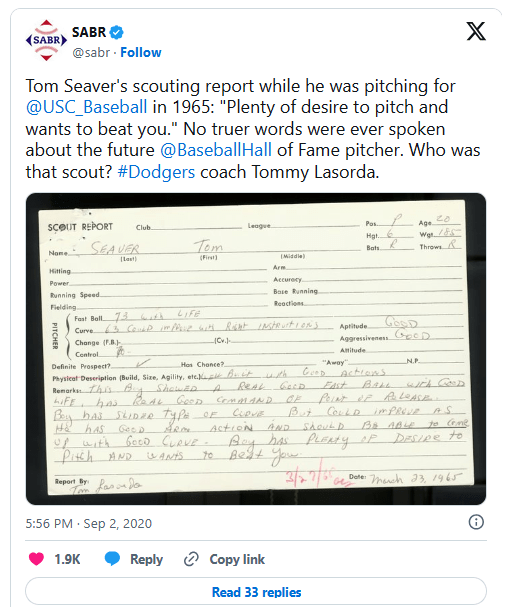

The 1994 Major League Baseball season started with Don Yi wearing the No. 94 jersey for the Los Angeles Dodgers.

It wasn’t necessarily the Year of Yi in Dodgertown that particular season, but numerically, it made sense.

While Yi was neither bat boy, ball dude nor clubhouse attendant, the 31-year-old UCLA graduate and computer programmer spoke South Korean. The Dodgers in general, and Chan Ho Park, more specifically, could use Yi’s skill set.

As an important part of a contract stipulation when the Dodgers signed a $1.2 million landmark deal with the 20-year-old pitcher, announced at a press conference at a hotel in Koreatown, the team would provide an interpreter.

Where Yi came into the picture, it’s somewhat a mystery.

Park, as the first MLB player brought in from South Korean player, needed to acclimate and assimilate. Yi was there to accomodate. This new-fangled job would evolve, or go sideways, on a daily basis.

It started with this: What is Park’s name?

The first time Yi was in full uniform as the team arrived its Vero Beach, Fla., training camp in March of ’94, reporters and teammates wanted to know what to call him.

“Some people are calling him Mr. Ho,” said Yi.

Dodgers broadcaster Ross Porter called him “Park Chan-ho,” as per Korean custom to use the family’s given surname first. Park asked if Yi could help him get the media covering him to “Americanize” his name.

Once that box was checked, what else might get found in translation?

Continue reading “No. 94: Don Yi”